Overview

Early Career and Achievements in Sindh

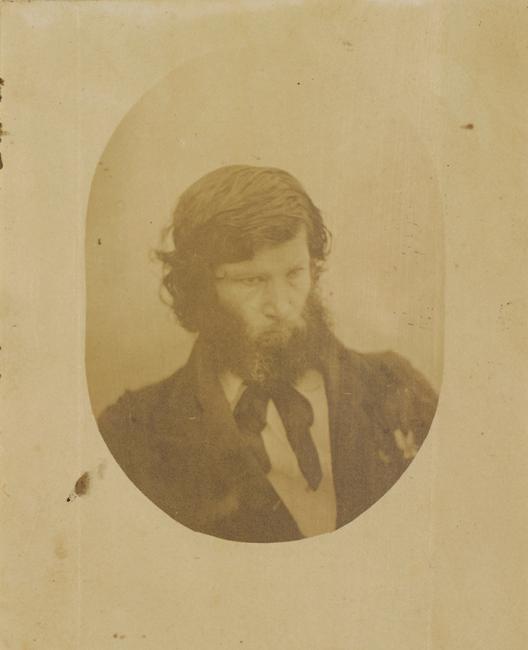

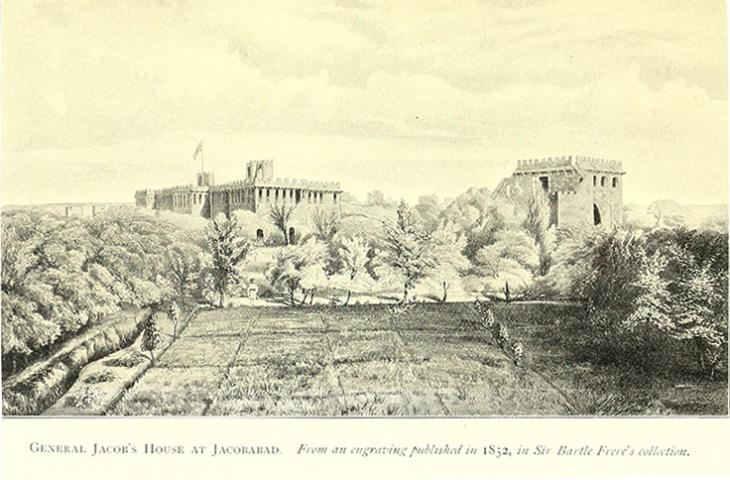

British East India Company officer John Jacob is primarily known for his achievements as political and military governor in Upper Sindh, which in the 1840s and 1850s formed the “unruly” north-west frontier Region of British India bordering Afghanistan. of British-occupied India.

An expert administrator, innovator, and inventor, Jacob’s career and accomplishments, as well as his “eccentric” nature, are well documented. However, a close analysis of his papers in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. and European Manuscripts collections held at the British Library provides a number of lesser-known insights into a man who would brook no challenge, perceived or otherwise, to his authority.

The Anglo-Persian War (1856-57)

On 13 March 1857 Jacob arrived at Bushire [Bushehr], in Persia [Iran]. He had been summoned to assist his old friend Lieutenant-General James Outram, who was then commanding the British forces fighting against Persia. A few days later he was placed in charge of the forces at Bushehr, the previous incumbent having committed suicide, while Outram departed to fight in Mohammerah [Khorramshahr]. When news of an armistice (signed on 4 March) came in April, Jacob was charged with organising the British evacuation.

Rivalry between two British Public Servants

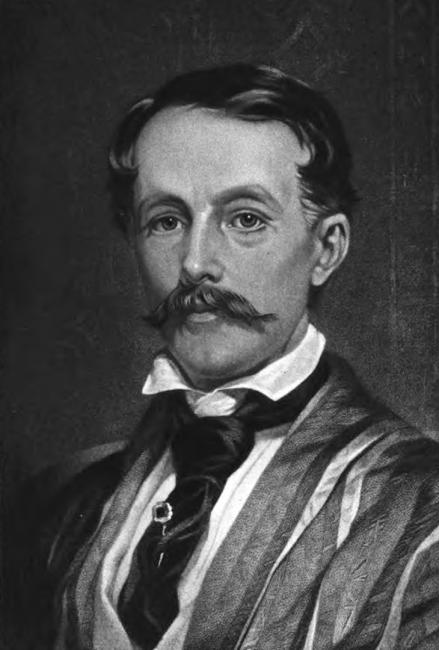

Jacob soon came into conflict with Charles Augustus Murray, HM Ambassador to the King of Persia. Murray, a well-travelled diplomat with a privileged, aristocratic background, contrasted with Jacob, whose background and means were modest.

Murray and Jacob clashed repeatedly over which of them was the superior representative of the British Government at Bushehr, and over the timing of troop shipments back to India. Their quarrels soon spilled over into other operational matters.

The Mirza Agha Affair

In April, Jacob dismissed Mirza Agha, an official deputed by Mirza Muhammad Khan Qajar Davallu, the Persian Commander-in-Chief, to liaise with Jacob. Mirza Agha, who was also Persian Secretary to Murray at the British Embassy, had complained about being discourteously received at the British camp. Jacob reacted indignantly, calling the complaint ‘insolent and grossly improper’.

In a letter, Jacob pointedly instructs Mirza Agha to ‘understand that since Sir James Outram departed I have represented, and […] do now represent, the British Government at Bushire’ (IOR/H/549, f. 604v).

In his letters, Murray goes to great lengths to defend his secretary, arguing that he has neither been intentionally insolent nor deserving of the public censure and humiliation to which Jacob has subjected him. Writing to Outram to rebut the accusations, he refers to parts of Jacob’s letter as nothing but ‘abuse’ (IOR/H/549, f. 632r), and further adds that Jacob will now have to deal with a far less qualified and experienced secretary.

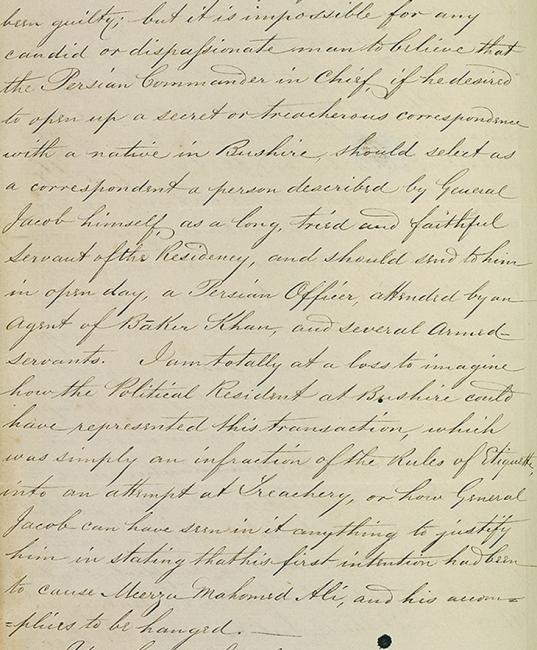

The Affair of the ‘Persian Spy’ Engineer Officer

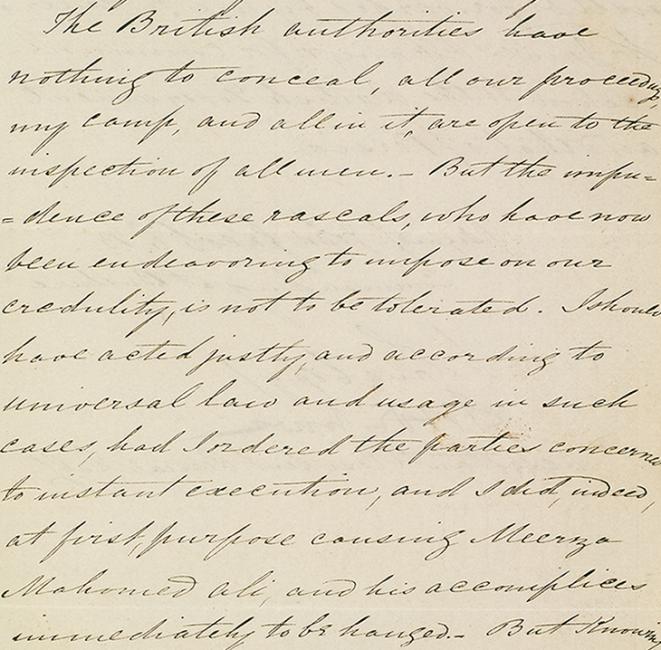

Tensions escalated in May 1857 when Jacob arrested and imprisoned two messengers ‒ one an Engineer Officer of the Persian Army – carrying letters from Mirza Muhammad Khan addressed to the Persian Secretary of Captain Felix Jones, the British Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. and Resident in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. . The intercepted letters included instructions that the Secretary make a plan of Bushehr and its environs. Conscious that the Anglo-Persian peace treaty remained unratified, and that his army was significantly outnumbered by the Persian forces encamped at Borazjan nearby, Jacob’s suspicions were aroused. Feigning a conviction that these letters were forgeries, he wrote angrily to the Persian Commander-in-Chief, declaring that ‘the British authorities have nothing to conceal’.

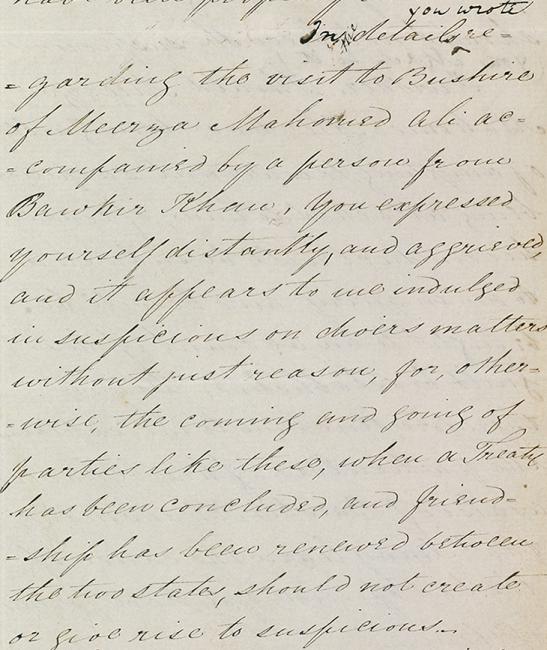

In his response, the Persian Commander-in-Chief attempts to placate Jacob, explaining that ‘the coming and going of parties like these […] should not create or give rise to suspicions’.

Reassuring Jacob that there was nothing improper about the visit (considering the Persian Army will be taking over the Bushehr garrison once the British have evacuated), Mirza Muhammad Khan reminds him that ‘friendship requires genial intercommunication and not severity that is freezing of relationships’ (IOR/H/550, f. 312v).

Murray, meanwhile, refused to forward copies of Jacob’s letters to the Persian Government at Tehran, fearing that they might re-inflame any residual tensions in Anglo-Persian diplomatic relations.

Anglo-Persian Relations Renewed but the Jacob-Murray feud continues

Jacob subsequently released the Persian Engineer Officer, and later in June there was a thaw in relations between Jacob and the Persian Commander-in-Chief. On the initiative of Outram and Mirza Muhammad Khan, each military camp sent a high-ranking emissary to the other - Haji Shaikh Muhsin Khan, Sarhang of the First Order, and Henry Willoughby Trevelyan, Brigadier Commandant of Artillery in Persia. The visits resulted in highly complimentary reports by both parties, notably Trevelyan’s account of lavish hospitality, and vignettes of the senior military officers in the Persian camp (IOR/R/15/1/174, ff. 3r-53v). In his letters, Jacob similarly expresses respect and amicability towards Mirza Muhammad Khan, writing: ‘If I should hereafter have the happiness of meeting your Excellency whether in Persia or elsewhere I trust that we shall meet as friends’ (IOR/15/1/174, f. 118v).

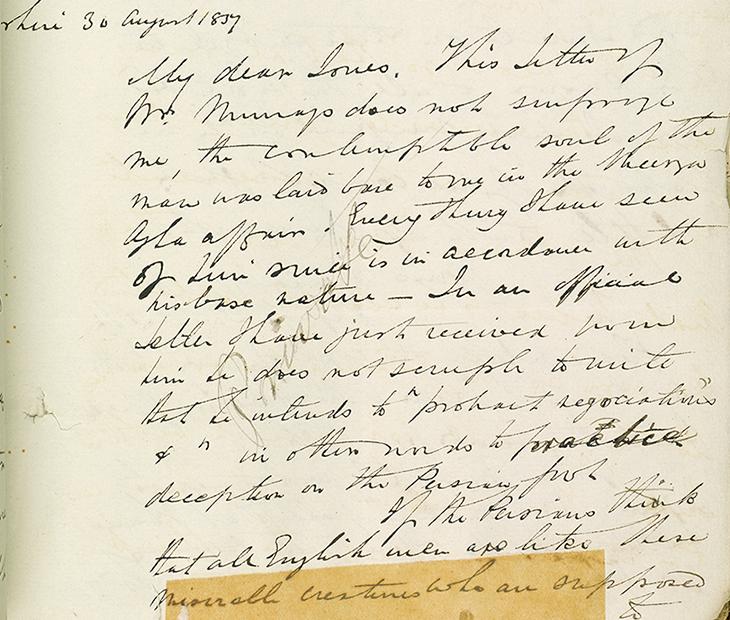

There was however no such warming in Jacob’s feelings towards the Ambassador to Persia. When Murray warned Captain Jones on 17 August 1857 of an alleged Persian plot to attack British troops embarking at Bushehr, Jacob responded with scorn, arguing that the duplicitous diplomat was trying to protract negotiations with the Persian Government. In a letter to Jones, he says: ‘This letter from Mr Murray does not surprise me, the contemptible soul of the man was laid bare to me in the Meerza [sic] Agha affair. Everything I have seen of him since is in accordance with his base nature’.

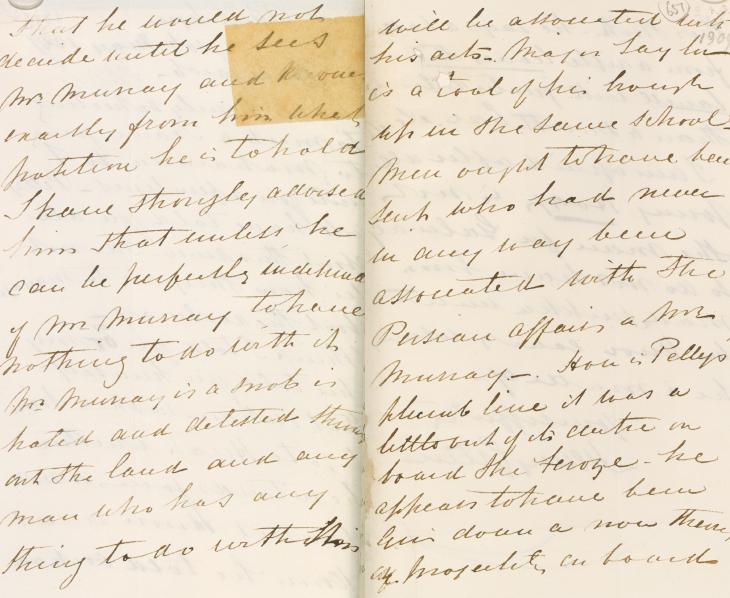

While Jacob’s views on Murray were in keeping with his general lack of respect for the ‘smooth words, low cunning, and present-making [of] clever and cunning diplomatists’ (8023.d.37., p. 382), there is evidence that others in Sindh circles also regarded Murray with contempt. In a letter to Jacob, Major Henry Green, Political Superintendent Frontier Upper Sinde, writes that he is advising a colleague not to accept any position associated with Murray, whom he calls ‘a snob […] hated and detested throughout the land’.

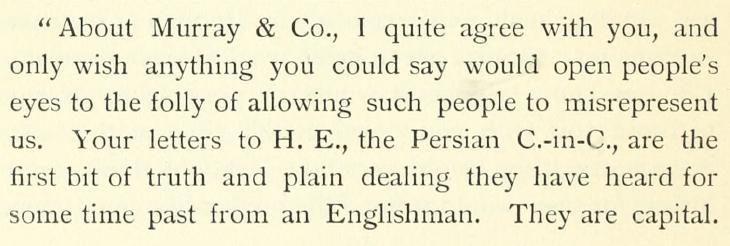

This view is seemingly also endorsed in a letter from the Commissioner in Sindh to Jacob.

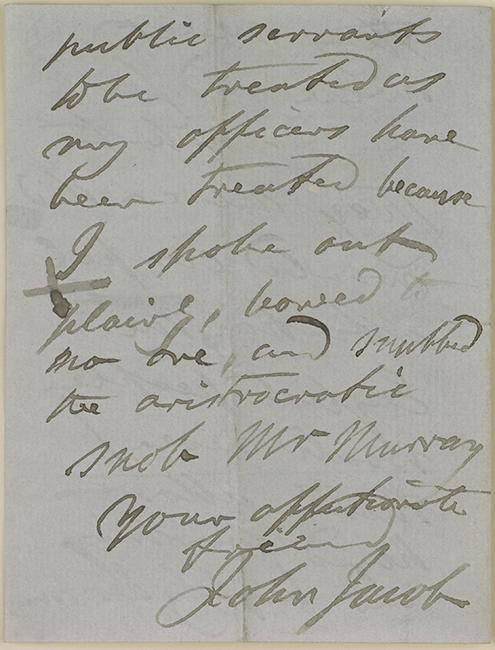

Epilogue 1858

Back at his post in Sindh, in December 1857, an official letter arrived for Jacob from Lord Clarendon, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, entreating the two public servants to ‘allow any differences which may have arisen to be buried in oblivion’ (IOR/H/550, f. 396v). Evidence shows, however, that Jacob retained his strong opinions of Charles Murray. In a letter to Lewis Pelly dated 4 June 1858, he fulminates that the British Government has ignored his recommendations for bravery in the Persian Campaign ‘because I spoke out plainly, bowed to no one, and snubbed the aristocratic snob Mr Murray’.