Overview

Climactic Extremes

Comments about the weather and the climate appear frequently in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records, mostly noting its ill-effects on the health of those writing. Some of the most extreme weather appears in an item written by the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Turkish Arabia A term used by the British officials to describe the territory roughly corresponding to, but not coextensive with, modern-day Iraq under the control of the Ottoman Empire. , Claudius James Rich. Writing in August 1819, he vividly describes the misery of the people in Baghdad, as the heat grew to such an extent that rain turned to steam as it hit the ground. However, as with many letters from British agents, there is an element of exaggeration in Rich’s account, not least his thermometer readings, which he claims reached 188 degrees Fahrenheit (87 degrees Celsius) at midnight outside. As the highest recorded temperature on earth is 136 °F (58 °C), it is likely that either Rich’s thermometer or his eyesight was faulty.

Deaths at Bushehr

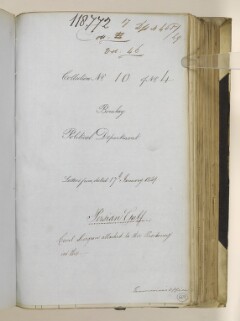

Uncomfortably high temperatures were not the only problem for British officials. Illnesses could strike suddenly, and the length of time needed for communications could mean that deputies unexpectedly had to step in when their superiors died. This was the situation for Assistant Surgeon Colin McTavish at the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. in September 1823. Having left Basra himself on account of poor health, McTavish arrived at Bushehr to a depleted team. Captain John Frederick Soilleux of the 1st Regiment Cavalry based in the city had died in August, followed by the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. Surgeon, Dr Edward Milward, two days before McTavish’s arrival. This left only the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. himself, Captain John McLeod, who contracted a fever on 13 September and died a week later. These three deaths in quick succession resulted in the relatively junior McTavish being left in sole control of the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. , until the Senior Naval Officer in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , Captain Henry Hardy, could arrive.

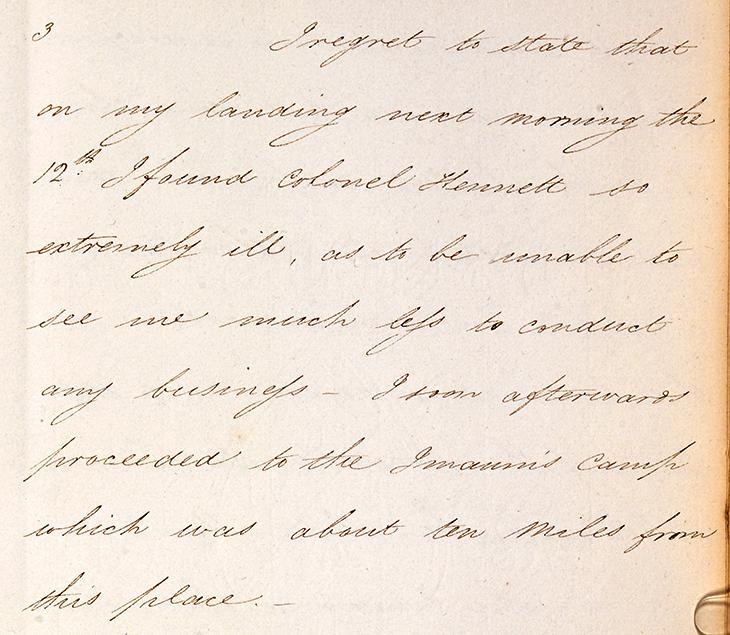

McLeod had only been in post as Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Gulf since December 1822 when he had replaced William Bruce. Bruce had been prevented from returning to India until McLeod arrived, due to the death of Assistant Surgeon Todd, meaning there was no one to whom Bruce could hand over the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. . McLeod had faced issues too, being unable to gain as much information as he would have liked when he stopped at Qeshm, as the Acting Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. there, Colonel Brackley Kennett, was too ill to see him.

Deaths at Muscat

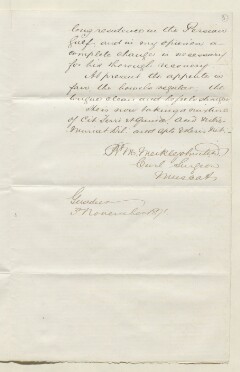

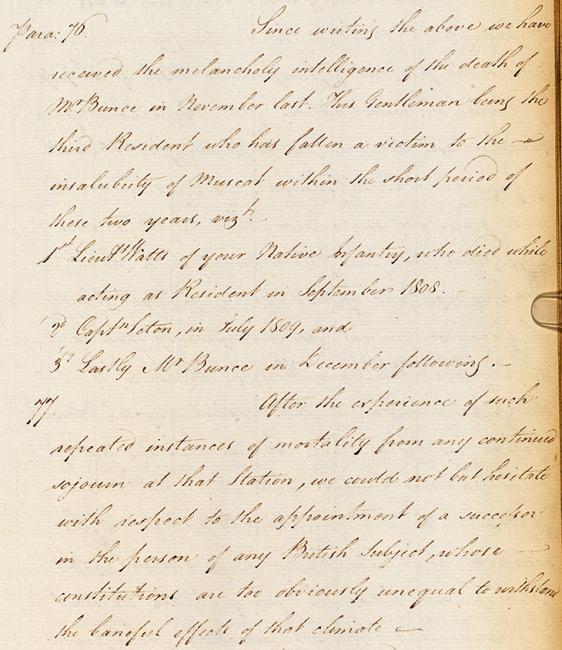

Bushehr was not the only place where death roamed the rooms of the British Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. . The situation in Muscat was so alarming that after the quick deaths of two Residents in a row (Lieutenant Watts in September 1808 and Captain David Seton in July 1809), the Bombay Government decided against appointing another. However, William Bunce insisted that he could take the position, with a yacht allowance to allow him to escape the oppressive climate if necessary. This was a foolhardy decision as he, too, died within a few months. After his death in November 1809, the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. decided that they could not appoint any more European officers there, and instead merged the Bushehr and Muscat Residencies.

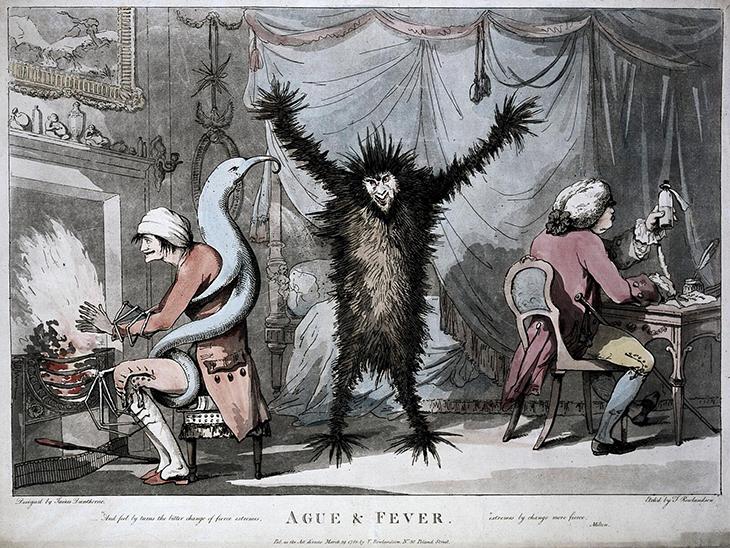

“Bad Air”

Lacking the medical knowledge to identify heatstroke or certain diseases, British officials often reported illnesses in vague terms. This makes it difficult to determine what caused the fevers that overcame so many British subjects. In both the records and medical treatises from this time, fever is often described as the disease itself, rather than a symptom. Prior to important pathological discoveries in the mid-1850s (such as germ theory and water contamination), medical professionals and the public alike blamed fevers and poor health on so-called “bad air”.

Alternatively known as miasma theory, the out-dated concept of “bad air” attributes symptoms of ill-health to any kind of polluted or noxious air (such as overcrowded slums in Britain). However, the records abound with descriptions of the Gulf’s air as particularly ‘baneful’, ‘prejudicial’ and ‘deleterious’ for the European constitution (IOR/F/4/343/7960, f. 98r; IOR/F/4/905/25661*, f. 8r [not currently on QDL]; IOR/F/4/416/10296, f. 328v). Dr William Campbell, Surgeon at the Gulf Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. , was of the opinion in 1848 that a hot climate was ‘an active cause of disease’ (IOR/F/4/2302/118772, f. 697r). In addition to the heat, the air in the Gulf was also very humid, and this combination was thought by some to be harmful to a person’s blood and internal organs – although British sources are inconsistent in their consideration of whether this impact was universal, or only affected Europeans.

That the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. stopped appointing British Residents in Muscat reflects the belief that there was no cure or treatment for sickness caused by a ‘baneful’ climate, except leaving the region. In Captain Seton’s case, surgeons had recommended he return to Europe in 1808, a year before his death. Medical officers frequently advised a “change of air” for their patients, and officers often reference this in their requests to be relieved of their duties.

Mad Dogs and Englishmen

Later in the nineteenth century, knowledge about the causes of illnesses was growing. In his notes published in 1853, Colonel William Henry Sykes, member of the East India Company Board of Directors, reports that two naval officers had observed a link between diet and water supply, and the prevalence of fever among European sailors visiting Zanzibar. Sykes also highlights the importance of learning from the inhabitants of hot and humid climates, stating that ‘a good deal of the mortality which occurs amongst Europeans in intertropical regions is partly to be attributed to the inflexibility of European habits’, suggesting that adopting the diets, clothing, and routines of locals would be beneficial (Sykes, p. 115). Surgeon James Johnson offers similar guidance in a treatise first published in 1818, although his advice also includes white supremacist comments on ‘indigenous customs’, which he deemed ‘ludicrous’ (Johnson, p. 495).

Sykes and Johnson’s attitudes demonstrate a shift from viewing the Gulf’s climate as inherently inhabitable for Europeans, to acknowledging the need for Europeans to adapt. Citing the annual loss of European troops in India as 5.5%, compared to only 2% of Indian troops, Sykes suggests that the climate has been often wrongfully accused and that ‘the accusation ought properly to rest upon the accuser’ (Sykes, p. 115).