Overview

Introduction

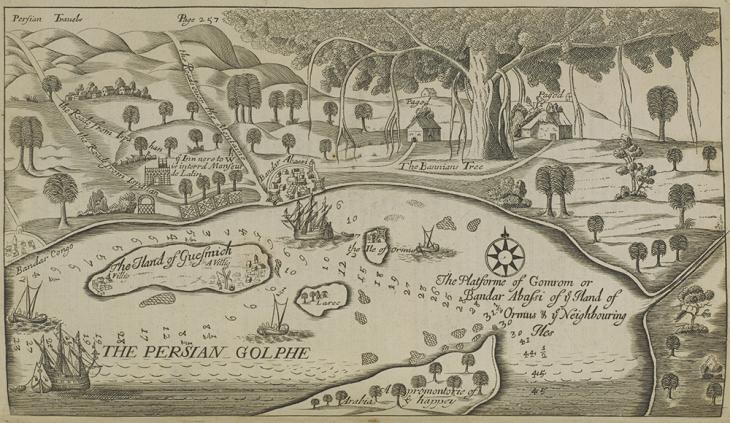

From 1627-1630, the English government official Thomas Herbert travelled as part of a diplomatic mission to Safavid Persia [Iran]. He later published an account of his trip in which he describes the ‘Bannyans’ as ‘the aborigines of these parts’ who ‘swarm throughout the Orient […] pursuing trade in infinite numbers’. He further recounts a trip to see a large, sprawling tree just outside the town of Gombroon [Bandar-e ʻAbbas]. This tree, he recalls, went by various names: ‘The arched Fig-tree some, arbor de rays or Tree of roots others call it; other some the Indian and de Goa; but we the Bannyan, by reason that they adorn it according to fancy; sometimes with ribbons, sometimes with streamers of varicoloured Taffata [taffeta, from the Persian tāftah]’ (215.e.12., p. 115). Banyan Merchant of Indian extraction. is still the name for this type of tree in English but who were the people after whom it was reportedly named?

Who were the Bania?

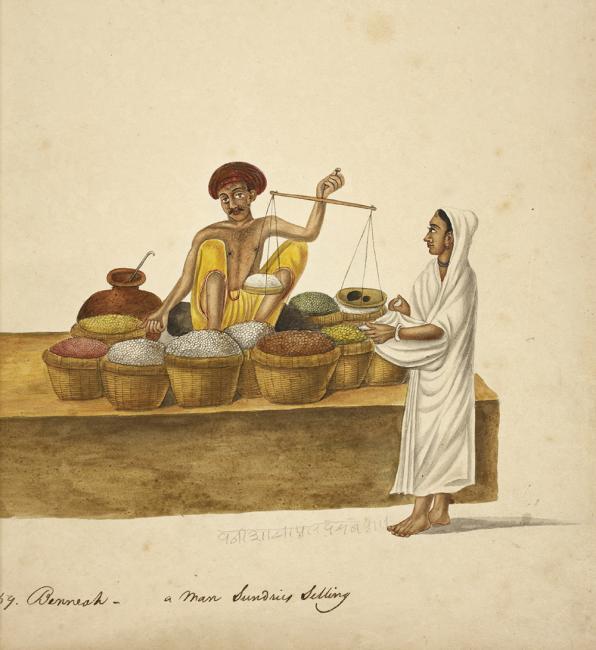

Bania Merchant of Indian extraction. was the term used by British merchants and officials to refer to South Asian expatriate merchant communities in the Gulf. Originally Sanskrit, then mediated through Hindi, Urdu, and other local vernacular languages, the term (also written as Banian Merchant of Indian extraction. and Banyan Merchant of Indian extraction. ) is the Anglicised form of the loan word in Persian, the language of official administration in pre-modern South Asia. It referred originally to a group of castes defined as agriculturalists. However, over time they diversified into trade, and subsequently took on a varied range of ancillary services and professions, including shop keeping, brokerage, moneylending, banking, and accountancy, as well as translation, secretarial, and official services, such as intelligence gathering.

While the term was used by British officials in South Asia to describe this group, in the Gulf Bania Merchant of Indian extraction. seems to have been applied to South Asian communities more generally, despite the fact that these communities included people of various occupational, caste, religious, and geographical backgrounds. The meaning and significance of the term as it appears in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records warrants careful consideration.

“Bania” in the India Office Records

The Gombroon Diaries and Consultation Books of the East India Company, from the start of the eighteenth century, contain references to ‘Banians’ passing on information and acting as brokers for the EIC. The Gulf “Bania” acted as agents for traders from several European countries, a practice that continued well into the nineteenth century. Their long-established prominence in all aspects of Gulf commerce made them indispensable to EIC efforts to establish a trading presence in the region. As Britain sought to assert itself more forcefully in the early nineteenth century, the interests of “Bania” merchants were sometimes cited among British justifications for the military interventions of 1809 and 1819.

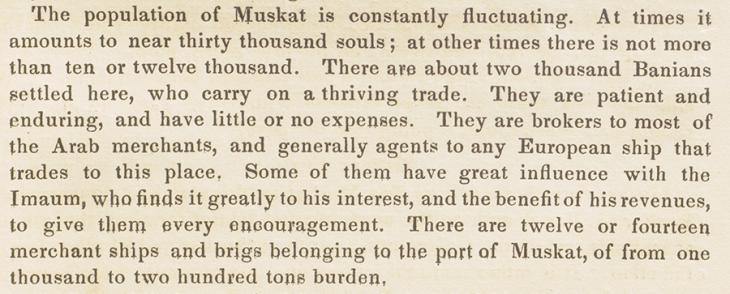

Subsequently, during the 1820s, the Indian Navy carried out a detailed survey of the coastline of the Gulf. One of its surveyors, Captain George Brucks, published his observations of the ports he had visited, including a description of Muscat, stating that ‘there are about two thousand Banians settled here, who carry on a thriving trade.’

Brucks’ account also records the presence of around a thousand ‘Banians’ from Sindh and Kachchh at nearby Matrah, as well as several smaller such communities in other Gulf ports ‘settled here for the purpose of trade’ (IOR/R/15/1/732, p. 629). Clearly, the “Bania” were vital for trade operations in the Gulf.

However, the prominence of South Asian merchant communities in Gulf commerce led to friction with local Arab rulers, and the IOR contain frequent cases of “Bania” appealing for protection on the basis of their status as subjects of British India. For example, one record details the 1845 case of a “Bania” called Seyt Hirjee [Sīth Hīrjī]. He had held the office of farmer of customs in Muscat, but was dismissed by the Governor. Claiming to have been threatened by his creditors, he fled to Khawajah Hizqil bin Yusuf, the Native Agent Non-British agents affiliated with the British Government. at Muscat. The Agent was later rebuked by Major Samuel Hennell, the Resident in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , for offering protection, as it was not deemed a case that merited British intervention. In 1858, Felix Jones, Hennell’s successor as Resident, reiterated this policy, and in doing so exposed his low opinion of “Bania” and their operations in the Gulf. He states that ‘ordinary transactions […] should not come under the consideration of the British Resident’ since they are conducted ‘in a complicated and usurious manner, peculiar to a needy population on the one hand and a highly speculative and exacting class like the banians on the other’ (IOR/L/PS/20/C91/2, p. 2088).

This comment sheds light on the use of the term by British officials in the Gulf. Bania Merchant of Indian extraction. should be seen as part of a repertoire of terms and phrases used to aid the identification and differentiation of non-European people for mainly British readers. Despite their long-standing presence, the “Bania” represented for the EIC a peripatetic minority without roots in the Middle East region, and were treated as apart from their Persian, Turkish, Arab, or African peers in host societies. The name therefore accrued multiple layers of meaning and its use in the IOR references a library of context-specific connotations denoting caste, religious, regional, and racial identities, in addition to mercantile and ancillary professions. This in turn perpetuates certain cultural attitudes and stereotypes.

For example, in 1838, following a visit to the port of Berbera, Lieutenant James Wellsted of the Indian Navy wrote in sweeping and derogatory terms about the “Bania”, claiming that, ‘Between Basrah [Basra] in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. and Hodeïdha [Al Hudaydah] in the Red Sea, almost every town on the coast of Arabia contains several families of this wily race’.

![Excerpt from Wellsted, accusing the ‘Banians’ of trying ‘to throw a veil of mystery over their proceedings, and to exclude other classes […] from any participation in their gains.’ Travels in Arabia, Vol. II (London: 1838), p. 368. Public Domain](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/003886801_000866_crop_web.jpg?itok=6hG1eTgK)

Wellsted’s description is illustrative of several recurring British characterisations of “Bania”, including their alleged craftiness, secrecy, and greed. Though rarely expounded in this sort of detail, such characterisations are pervasive in more subtle ways across the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records.

This is evident in the case of Seyt Hirjee. His title, a Hindi term for a high status businessman, and the role he occupied supervising the Muscat customs, both indicate that he was a person of considerable social standing. However, in their correspondence, British officials drop his title and call him simply ‘Hirjee’ or ‘Hirjee Banyan’. The result diminishes his social position and foregrounds his cultural and racial background above his professional status. This example illuminates how, in the IOR, the identities of individuals are regularly flattened into a broad category of “Bania”, which is often defined in negative and condescending ways.

Conclusion

The term Bania Merchant of Indian extraction. appears less and less frequently as the IOR material approaches the twentieth century, replaced either by general references to ‘Indian merchants’ or by other terms designating an individual’s specific function or occupation. It is unclear why the term fell out of use. It was perhaps a result of British officials’ growing familiarity with South Asian communities in the Gulf, and with the terms and names that distinguished them from each other.

Nevertheless, the widespread use of the term Bania Merchant of Indian extraction. for three hundred years to designate South Asian merchant communities in the Gulf testifies to the long-standing prominence of these communities in all aspects of Gulf commerce, and the EIC’s dependence on them as it sought to gain a foothold in the region. Furthermore, it is a reminder that the IOR need to be read critically through the prism of the ideas prevailing among colonial officials of the time, particularly those relating to racial, cultural, and national distinctions. Within this worldview, “Bania” communities were singled out as ‘other’, as indicated by the systematic use of distinctive terms of description.