Overview

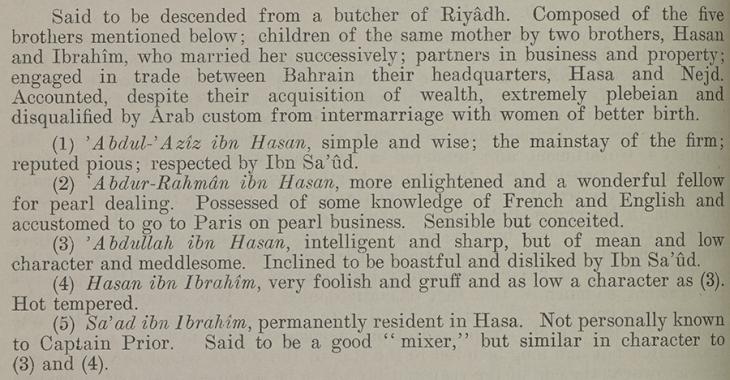

The Qusaybi (or Algosaibi) family became one of the most prominent, wealthy, and influential merchant families in the Gulf in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1930, the British Minister at Jeddah, Andrew Ryan, described them as ‘not only the chief pearl merchants of the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , but […] also the chief financiers of Ibn Saud’s regime’ (IOR/R/15/1/567, f. 27r). For several decades, the brothers ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, ‘Abdullah, ‘Abd al-Rahman, Hasan, and Sa‘d al-Qusaybi yielded significant political, financial, and economic influence.

Family background and business operations

References to ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, ‘Abdullah, and ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Qusaybi appear in many files on the QDL, in papers dating from around 1911-1953. The family name is variously spelled Algosaibi, al-Gosaibi, Qusaibi, Qosaibi, or Qasaibi in English-language papers. Some files include correspondence from ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and ‘Abdullah (mostly in Arabic, sometimes with English translations), and letters from ‘Abd al-Rahman, which are in English.

Following a drought in Najd, their father Hasan moved with his brothers Muhammad and Ibrahim from Huraymila to the Gulf coast around 1885. There they continued working with camels, transporting goods. Muhammad then relocated to Bahrain and worked as a clerk for a pearl merchant before setting up his own successful business in the same industry. After Hasan’s death, Ibrahim married his widow, and had two sons with her, Hasan and Sa‘d.

In about 1898, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, ‘Abdullah, and ‘Abd al-Rahman joined their uncle Muhammad in Bahrain. From there, he sent each of them to India to learn English, buy foodstuffs, and deal with Bombay [Mumbai] pearl merchants. Meanwhile, using the profits from the Qusaybi offices in Bombay and Bahrain, Ibrahim acquired extensive date gardens in Al-Ahsa. In about 1906, Ibrahim met and befriended Ibn Sa‘ud while travelling on pilgrimage [Hajj], and in 1908 the family started carrying out assignments for him. It was after Ibn Sa‘ud had conquered Al-Ahsa in 1913, and established a presence on the Gulf coast, that their relationship became closer and their services more valuable to him. By this time the family business was mainly being run by the five brothers, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, ‘Abdullah, ‘Abd al-Rahman, Hasan, and Sa‘d.

They were all partners and had their own roles in the business. As head of the family, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz managed the Bombay-Bahrain importing operation. ‘Abdullah and Hasan dealt with various business, while ‘Abd al-Rahman was the family’s main pearl dealer, assisted by Hasan. Travelling regularly to Bombay and Europe, ‘Abd al-Rahman sold pearls and carried out assignments for Ibn Sa‘ud. Sa‘d mostly stayed in Al-Ahsa, but the other four brothers moved between Bahrain, Al-Qatif, Al-Ahsa, Riyadh, Al Jubail, and India.

Agents of Ibn Sa‘ud

The Qusaybis acted as Ibn Sa‘ud’s agents in Bahrain, providing a channel for diplomatic communications with British officials (see e.g. IOR/R/15/1/334, ff. 61r, 79r; IOR/R/15/2/89; IOR/R/15/2/140). They were moreover the conduit for Britain’s £5,000 monthly subsidy to Ibn Sa‘ud during the First World War, and also dealt with his arms and ammunition supplies. In 1919, Ibn Sa‘ud’s son Fayṣal undertook an official visit to London, and Ibn Sa‘ud insisted that ‘Abdullah accompany him. When Ibn Sa‘ud sought to employ a British bank as a state bank in the Hejaz in 1931, he sent ‘Abd al-Rahman to London as his representative (see IOR/R/15/1/567, ff. 85r-86r; IOR/L/PS/12/2073, f. 352r; IOR/L/PS/12/2085, f. 222v).

The main aspect of the family’s work for Ibn Sa‘ud, however, was buying supplies he required for Najd. They established a virtual monopoly on the carrying trade between Bahrain and the Arabian mainland, growing increasingly wealthy and becoming probably the richest family in Arabia in the 1920s.

They benefitted from the trade blockade that Ibn Sa‘ud imposed on Kuwait from 1923 to 1937, as they persuaded him to divert trade routes to Al Hofuf, Al Uqayr, and Bahrain, where they were very economically influential. According to the British Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. in 1935, Lieutenant Colonel Trenchard William Craven Fowle, the Shaikh of Kuwait regarded ‘Abd al-‘Aziz as ‘the prime instigator’ of the blockade (IOR/R/15/5/111, f. 97r).

With their increasing wealth and prestige, the Qusaybis also gained political influence in Bahrain. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz was a member of the Manama Municipal Council for over thirty years from its formation in 1920. Initially Britain viewed the Qusaybis as useful allies, and in 1922 ‘Abd al-‘Aziz was awarded the honorific title of Khan Bahadur (for services rendered to the British crown). However, relations between Ibn Sa‘ud and Britain began to deteriorate in the early 1920s, and British officials became concerned about the Qusaybi family’s role as Ibn Sa‘ud’s agents in Bahrain. A series of issues brought the Qusaybis into conflict with British officials (e.g. see IOR/R/15/1/319, ff. 177r-181r).

The 1923 Disturbances in Manama

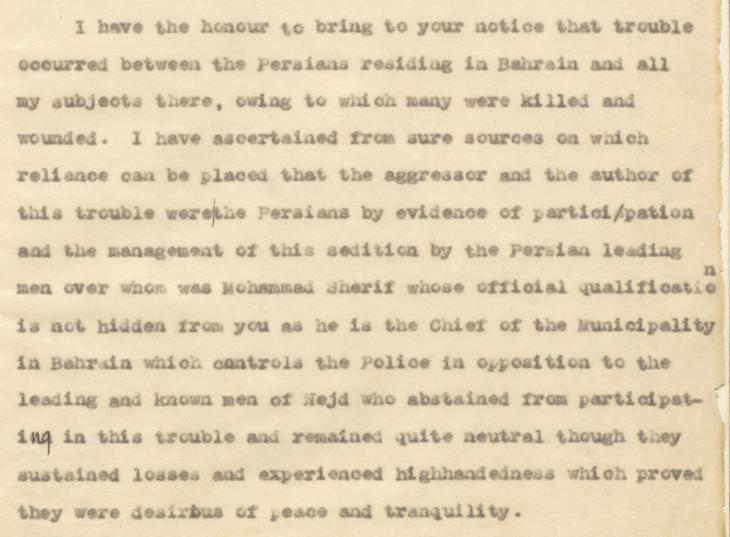

In April 1923, a fight outside the Qusaybi offices in Manama in Bahrain led to a general fracas between members of the Najdi and Persian [Iranian] communities. Large scale clashes ensued from 10 to 12 May. Following this disruption of public order, Shaikh ‘Isa bin ‘Ali Al Khalifah was deposed by Britain and replaced by his son and heir apparent, Shaikh Hamad, a change intended to enable administrative reforms to be carried out.

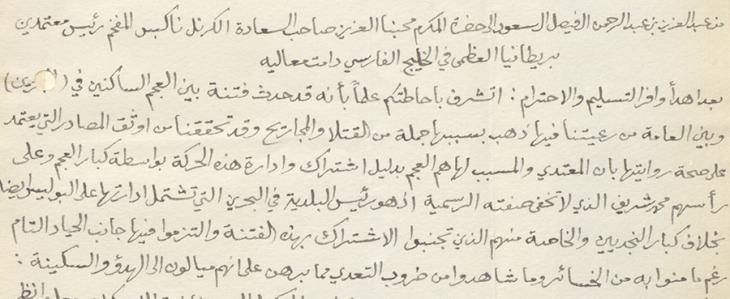

In a letter to Ibn Sa‘ud of 18 May 1923, the then Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. , Arthur Prescott Trevor, asserts that the Najdis were the aggressors, and that ‘Abdullah al-Qusaybi had been ‘primarily responsible’ for inciting them (IOR/R/15/2/101, f. 8). Ibn Sa‘ud, on the other hand, claims instead that the instigators were the ʻajam [literally ‘non-Arabs’, i.e. Persians], and that the (mostly Persian) police had sided with them.

Prior to these events, ‘Abdullah had been acting as Ibn Sa‘ud’s agent in Bahrain (during ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s absence in India). Trevor had stated to the Government of India that ‘Abdullah had been ‘arrogating to himself the position of Consul’ for Najdi subjects in Bahrain (IOR/R/15/1/334, f. 6r). In June 1923, Trevor therefore reminded Ibn Sa‘ud that Shaikh ‘Isa had previously committed to treaties with Britain, agreeing not to permit agents of any other government to reside in his territory, and that further, Ibn Sa‘ud himself had placed Najdi subjects in Bahrain under British protection in 1920.

Trevor promptly removed ‘Abdullah from Bahrain. Reporting after ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s return from India, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. at Bahrain, Major Clive Kirkpatrick Daly, notes that he ‘no longer constantly talks about being Bin Saud’s agent [and] does not interfere in affairs of Nejdi subjects as in the past’. He also suggests that ‘As long as Abdul Aziz continues to act as a purely private agent of the Sultan here […] he might be allowed to continue’ (IOR/R/15/1/334, f. 61r).

Financial Difficulties and Ibn Sa‘ud’s Debts

In a report from 1931, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. at Bahrain, Charles Geoffrey Prior, writes that the Qusaybi family ‘deal in every kind of merchandize [sic] but their principal lines are the import of grain and the pearl trade’ (IOR/R/15/2/101, f. 69r). The collapse of the pearling industry in the early 1930s weakened the family’s finances, which contributed to worsening relations with Ibn Sa‘ud. The family had advanced him money, and he had never paid directly for their services. British officials closely monitored Ibn Sa‘ud’s indebtedness to the family and relations between them. According to Prior, the brothers gave Ibn Sa‘ud an ultimatum in 1932 in an attempt to exact payment. Ibn Sa‘ud eventually summoned ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and ‘Abd al-Rahman to Taif in early 1933 to settle the account.

In 1939, Ibn Sa‘ud wrote to Shaikh Hamad asking him to treat the Qusaybis ‘with special kindness’ (IOR/L/PS/12/2076, f. 24r), and this was followed immediately by a request for permission to import a motor car free of duty. Fowle’s analysis was that Ibn Sa‘ud was still in debt to the family and therefore ‘trying to be generous to them by proxy’ (IOR/L/PS/12/2076, f. 25r).

Division of the Family Business

Increasing financial difficulties led to disagreements within the Qusaybi family. With the rapidly shifting economic landscape and the need to diversify their business empire, the brothers began to split. They established separate and independent companies, and in 1943 the family divided its assets, land, houses, and gardens. ‘Abdullah retired to Al-Qatif, Sa‘d remained in Al-Hofuf, and the other three stayed in Bahrain. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and his sons traded in food and consumer goods. In addition, they established Bahrain’s first cold store and ice-making plant, and opened the Pearl Cinema in 1948. Meanwhile, ‘Abd al-Rahman and his sons imported cars and durable goods (including arms and ammunition). ‘Abd al-Rahman also stayed in the pearl business, which survived due to a limited demand for natural pearls from Europe and the USA.

After ‘Abd al-‘Aziz died in 1950, his sons divided his business between them, selling their agencies and focusing on real estate. Meanwhile, ‘Abd al-Rahman’s elder sons also started branching off. By the mid-1950s, the Qusaybi family business had split into twenty parts. However, the family’s commercial fortunes later revived and the Qusaybis also regained their political influence, with family members serving in government posts in both Bahrain and Saudi Arabia. ‘Abd al-Rahman’s son Ghazi ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Qusaybi, in particular, was a politician, diplomat, poet, and novelist, who between 1976 and his death in 2010, held ministerial posts in the Saudi Government and served as Ambassador to both Bahrain and the United Kingdom.