Overview

Human civilisation has manufactured and traded indigo for many centuries. The vivid blue pigment is produced from the Indigofera genus of plants, indigenous to many tropical and subtropical parts of the world, including India. Indigo’s vibrancy, so scarce in the natural world, combined with its versatility as a dye, has made it a valuable and prized commodity.

Importance and Value

Indigo blue has many associations with different societies. In the Arab world, indigo blue has been associated with both good luck and inauspiciousness, and was used to dye clothes and as pigment for body paint by the tribes of the Arabian Peninsula, particularly during festivities and weddings. In her books describing journeys through southern Arabia in the 1930s, Freya Stark repeatedly drew the reader’s attention to the painted faces and indigo henna of the women of the Hadhramaut region. Indigo has also been used in Arab societies as a medicine, thanks to its reputed cooling properties.

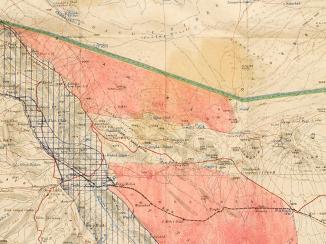

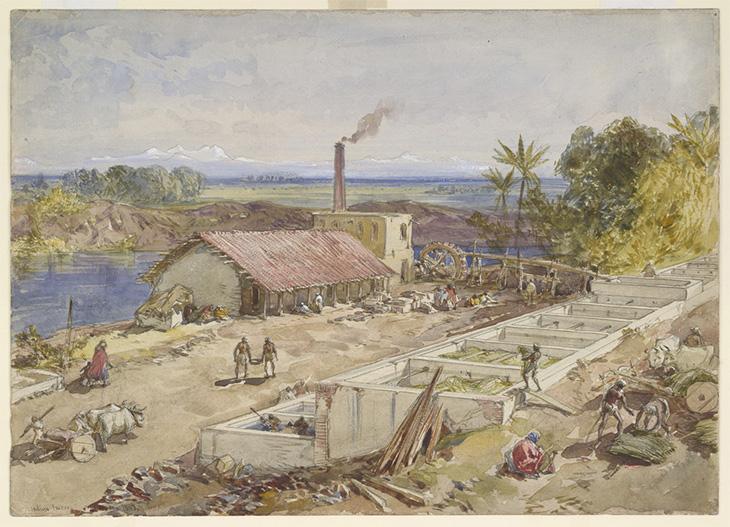

Because of its importance and high economic value, the European powers that colonised the Indian Ocean World in the seventeenth century (including Britain) were quick to exploit the demand for indigo. The agents of the East India Company instigated the large-scale, commercial production of indigo dye in Bengal. By the early nineteenth century Bengal was the principal producer of indigo in the world, its production and trade monopolised by Great Britain.

Shipwrecked and Destitute Seamen

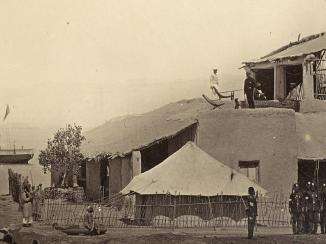

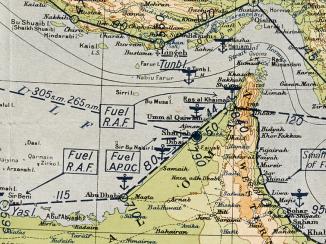

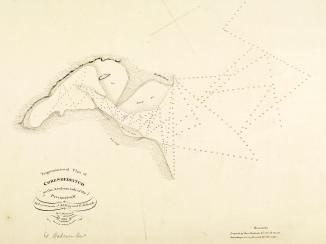

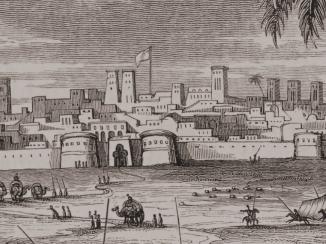

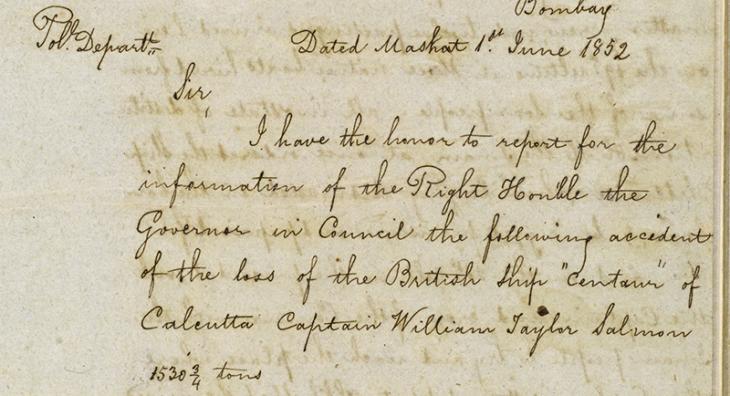

A series of letters in the Bushire correspondence books of the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records, written in the mid-nineteenth century, indicate the importance of indigo to Britain (as producer) and the societies of the Arabian Peninsula and the Gulf (as consumers). The letters tell the story of how, on 19 May 1852 forty-seven destitute and desperate seamen arrived at the British Government’s Political Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. in Muscat, having been shipwrecked a hundred and twenty miles off the coast two weeks previously.

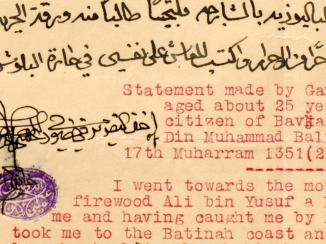

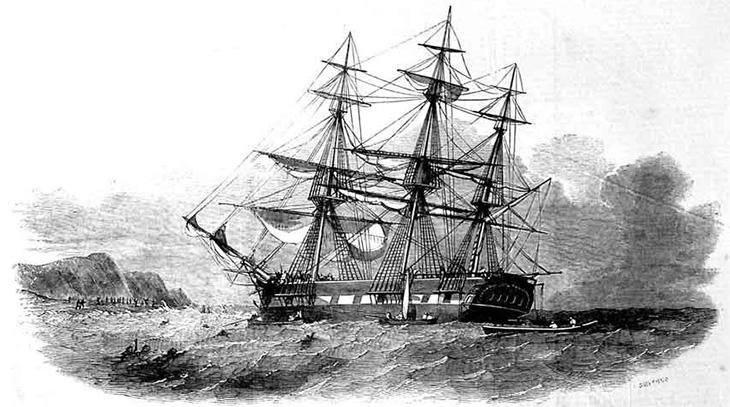

The plight of these seamen was one that was not unfamiliar to British officials based in ports around the Arabian peninsula in the nineteenth century – that of shipwreck and plunder at the hands of the native seafaring tribes. In this instance the unfortunate sailors, who had been carrying over 1600 casks of valuable indigo from Calcutta to Basra on the British merchant ship Centaur, ran aground at night in thick fog. Captain Salmon, the Centaur’s first officer, later recounted that when dawn broke, he and his crew found themselves at the mercy of the notorious Bani Boo Ali (Bani Bu Ali) tribe of Arabia, with whom the British had had a number of sometimes bloody clashes since the 1820s.

Unsurprisingly then, Salmon and his crew thought it prudent not to resist the tribesmen that had sailed out to meet them. For their part, the Bani Boo Ali allowed the crew to leave the ship with their lives, provided they left their precious cargo behind.

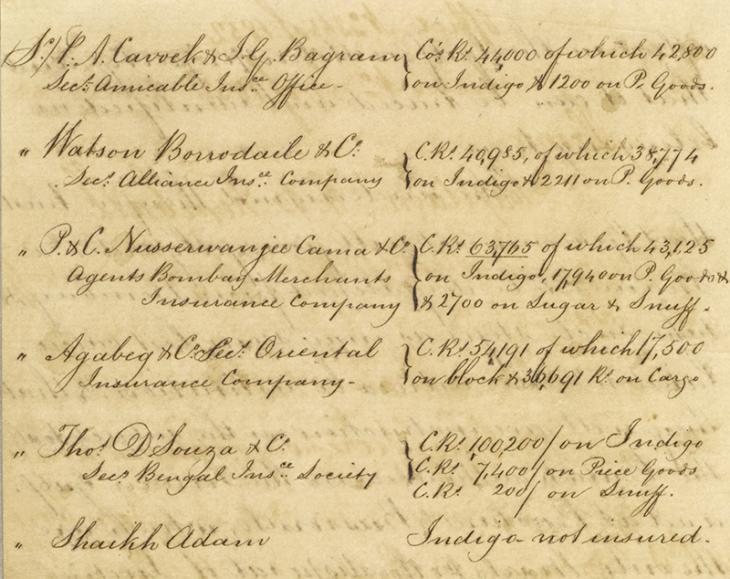

Two weeks later, when news of the Centaur’s plunder reached Muscat, British officials despatched a naval patrol to ascertain the shipwrecked vessel’s fate. All they found were the vessel’s charred remains, which had been completely stripped of its cargo and fittings. All 1645 chests of indigo were gone; many of them were found empty or smashed to pieces on the beach close by. The total value of the cargo of indigo was valued at twelve lakhs One lakh is equal to one hundred thousand rupees of rupees Indian silver coin also widely used in the Persian Gulf. . Five sixths of the cargo had been underwritten by insurers in India.

The loss of over 1600 casks of indigo was a huge blow to British traders in India and the Middle East. With a value of nearly £11 million in present-day terms, the Centaur’s cargo of indigo represented an entire season’s supply for the Gulf. So important was the Centaur’s indigo that, two years after the actual shipwreck and plunder had occurred, agents were still being employed by Government in Bombay to assist in the recovery of the missing goods.