Overview

For a period of over one hundred and fifty years, from 1820 until its withdrawal in 1971, Britain was the dominant power in the Gulf. Like many other European powers – notably the Portuguese, the French and the Dutch – Britain’s initial interest in the Gulf region, which began in the seventeenth century, was driven by the development of trade and commercial interests. The nature of Britain’s involvement began to change, however, after it consolidated and expanded its colonial holdings in India.

The East India Company

The key actor in both of these developments was the East India Company (EIC) – one of the largest and most powerful commercial entities to have ever existed. From the 1770s onwards, the EIC’s position in India developed from one of economic domination to political rule enforced by its own standing army and navy.

As the company’s possessions in India became increasingly lucrative, the surrounding region as well as the trade routes to and from India took on a newfound importance for the EIC. Accordingly, its involvement in the Gulf became increasingly direct and, although initially driven by a desire to protect its ships and employees in the region, it swiftly evolved into one of political control enforced by the use of military – primarily naval – force. In no small part these moves were motivated by Britain’s strategy of preventing rival imperial powers from gaining a foothold in the Gulf.

Tolls and Confrontation with the Qawasim

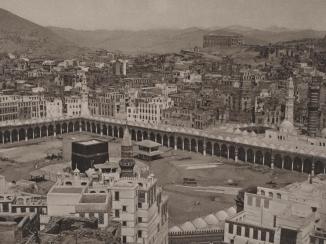

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the Strait of Hormuz, the entrance point to the Gulf, was controlled by the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. tribal confederation. The Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. had a large fleet of trading and military ships based alternatively at Ras al Khaimah and Sharjah. A key source of revenue for the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. was tolls, which they levied on all trade that passed through the Strait of Hormuz.

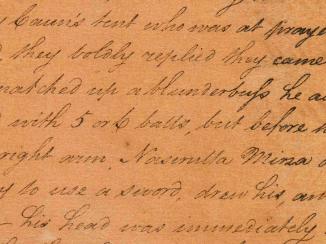

The British refused to pay these tolls and, unsurprisingly, serious tensions between the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. and the British began to develop. The British went so far as to refer to the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. as ‘pirates’. After a series of confrontations between the two sides in 1820, British forces laid siege to Ras Al Khaimah and destroyed the entire Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. fleet; this date marks the beginning of Britain’s hegemonic control over the region.

The General Treaty with the Arab Tribes of the Persian Gulf of 1820

After their crushing victory over the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. the British imposed an anti-piracy treaty on all of the Arab rulers in the region. To enforce the treaty, manage their relations with local rulers and protect British trade in the Gulf, the British created the post of Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. for the lower Gulf.

Originally based on Qishm Island, in 1822 the post was moved to Bushire on the Persian mainland and merged with the pre-existing position of EIC Resident at Bushire to create the position of Resident in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. ( Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. after the 1850s) the most senior British official in the Gulf and as such, the most powerful man in the region.

Further Treaties and the Formalisation of British Domination

Following the treaty of 1820, local Arab rulers agreed to a number of other treaties that formalised Britain’s dominant position in the region and limited their ability to act independently without Britain’s approval. The increased stability that this ‘Pax Britannica’ brought led to increased volumes of trade in the region. Ruling families began to actively seek British protection as a means of securing their rule and safeguarding their territories.

By signing the Perpetual Maritime Truce of 1853, the Arab rulers formally surrendered their right to wage war at sea in return for British protection against external threats to their families’ rule.

Following the Indian Rebellion in 1857, the British Government took control of the EIC’s possessions in India (thus beginning the formal British Empire in India) and from 1858 onwards assumed responsibility for maintaining the status quo in the Gulf.

Throughout the nineteenth century the British also signed a number of bilateral treaties with rulers of individual Arab shaikhdoms that gave Britain control over their foreign relations and made it responsible for their defence. Although British influence in Persia remained strong throughout this period, the ruling Qajar dynasty never formally surrendered its control over foreign relations and the level of political control Britain asserted over the various Arab shaikhdoms was never replicated in Persia.

Political Agencies, the Discovery of Oil and Indian Independence

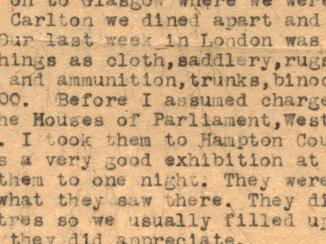

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, the dominant British position over the region was enforced by a naval military presence commanded by the Senior Naval Officer in the Gulf. British officials in the region had few qualms about ordering the occasional bombardment of the forts and palaces of Arab rulers if it was deemed that their actions were not sufficiently compliant with British interests. These officials operated from a network of political agencies that, at differing times, were located in Lingeh, Bahrain, Kuwait, Sharjah, Muscat, Doha, Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Gwadar, an Omani enclave in what is now Pakistan.

All of these agencies were co-ordinated by the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in Bushire until 1946 when the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. was transferred to Bahrain.

After 1947, and Indian Independence, the British Government in London became responsible for maintaining Britain’s position in the Gulf. By this stage, the discovery of enormous oil deposits meant that the Gulf region had taken on a geo-strategic significance of its own and its importance no longer lay in its relationship with – and proximity to – India.

Between 1913 and 1923 Britain had solicited assurances from the Gulf rulers that they would only grant oil concessions to companies approved by the British government. As oil deposits were discovered throughout the 1930s, they attempted to ensure that those concessions were only granted to British-owned companies. From the 1950s onwards, as the oil industry developed and the Arab states grew in wealth – notably Kuwait – the British encouraged the Gulf rulers to invest their surplus oil revenues in Britain.

By the late 1950s, British presence in the region was subject to growing criticism as Arab nationalist ideas grew in popularity throughout the Arab world. Although Kuwait became independent in 1961, Britain continued to dominate the Gulf for another decade until 1971 when it formally left the region and the other states on the Arab side of the Gulf received their independence.

While Britain relinquished its direct political control over the region, it retained a great deal of influence and to this day political, economic and military links between Britain and the Gulf States remain strong.