Overview

Berenice Catches Fire and Sinks

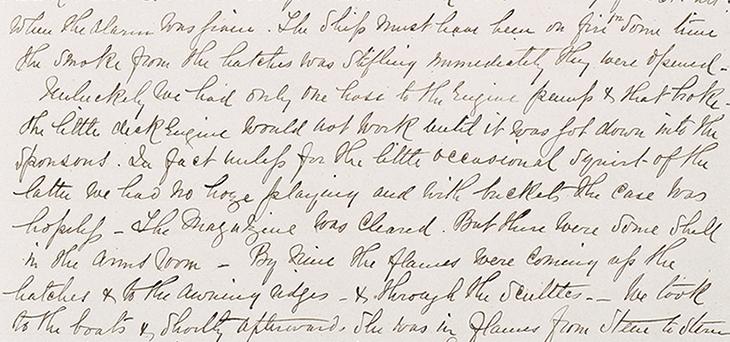

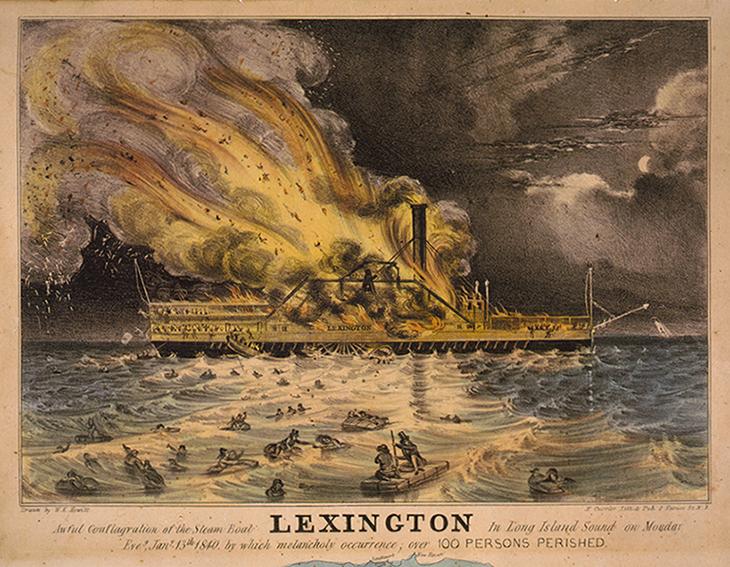

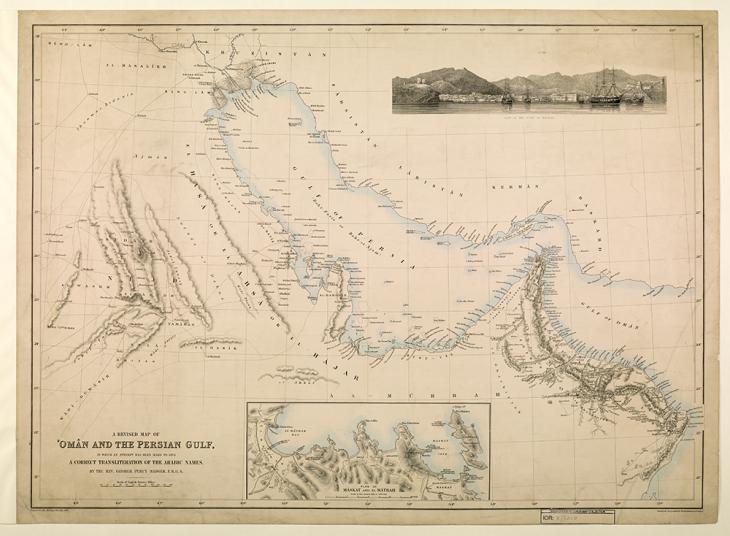

In October 1866 Major Lewis Pelly, the Resident in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , was on board the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. ship Berenice. While sailing down the Gulf to Muscat, a devastating fire broke out when the ship was twenty-five miles from Shaik Shaab Island [i.e. Shaikh Shu’ayb, or Bu Shu’ayb, now known as Lavan Island]. Writing to the Governor of Bombay, Pelly vividly describes the blaze: ‘The ship must have been on fire some time, the smoke from the hatches was stifling immediately they were opened. Unluckily we had only one hose to the engine pump & that broke […] the case was hopeless […] We took to the boats & shortly afterwards she was in flames from the stem to the stern’.

A night on a Gulf island beach

Having escaped in lifeboats with only the clothes on their back and a little bread and water, Pelly and the ship’s company and passengers spent the night on the shore of Shaikh Shu’ayb Island. Although the island was sparsely populated, it was not desolate, and Pelly and his companions were able to obtain more water and dates from a nearby hamlet before the men bedded down for the night on the beach (the women and children presumably slept in the boats). Situated approximately 200 miles southward along the coast from Bushehr, the island’s night-time temperature would have been between 21 and 28 degrees Celsius. As a seasoned traveller in Arabia and the Gulf region, Pelly was used to sleeping under the stars. Such consolations might well have taken the edge off the shock of watching the ship and his many possessions go up in flames.

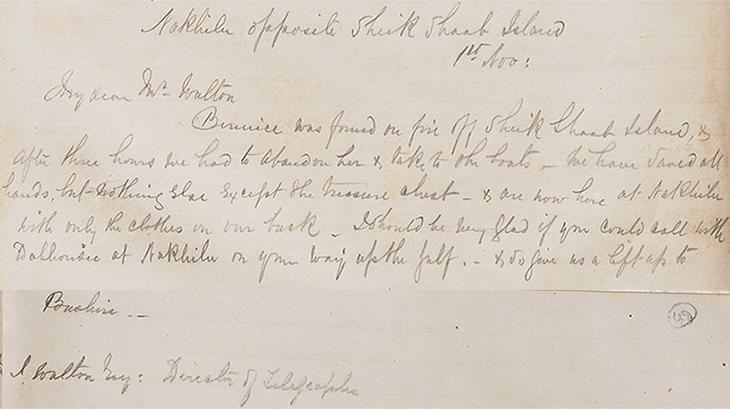

The following day, the company and passengers reached Nakhilu [Nokhaylo] on the Persian [Iranian] mainland opposite Shaikh Shu’ayb. From there Pelly, in conjunction with Captain Edwin Dawes (late Commander of Berenice) and his officers, began to organise their rescue.

Co-ordinating the rescue

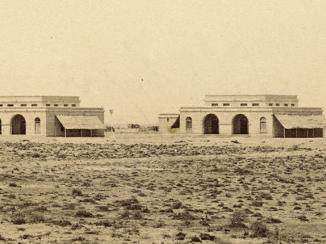

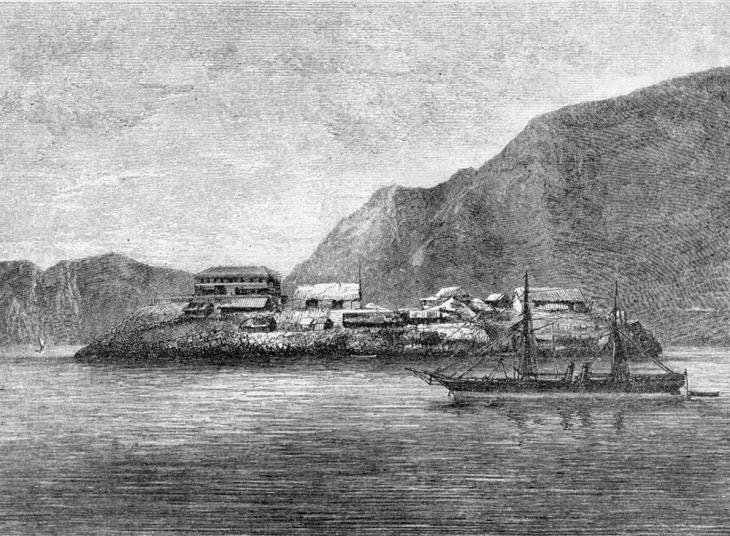

The events of 1-9 November are recorded in Lewis Pelly’s Private Papers, now held at the British Library. They indicate that over the next six days the party (or at least a portion of it) made its way ‘by native craft’ approximately 110 nautical miles eastward to the British naval and coaling station at Bassidore [Basaidu] on the island of Kishm [Qeshm] (Mss Eur F126/43, f. 48r). Along the way, they stopped at Khen Island [Jaziereh-ye Kish], Charrack [Bandar-e-Charack] and Lingeh [Bandar-e-Lengeh].

As the party sailed east, Pelly fired off numerous messages, urgently soliciting assistance from all possible quarters – government agents, local officials, naval and commercial sea captains – and informing the authorities in Bombay of the situation. His messages included the texts of telegrams to be sent, and were conveyed by Captain Dawes’s officers, travelling in small ‘bugarahs’ [baghlahs].

On 1 November, he addressed the Director of Telegraphs, Hubert Izaak Walton, requesting that he call at Nakhilu with the steamship Dalhousie ‘on [his] way up the Gulf’ and ‘give [them] a lift up to Bushire’.

Still at Nakhilu the following day, Pelly also wrote to the Commander of the gun boat HMS Clyde, requesting that he ‘be so good as to come with the ship under [his] command’. Preparing for the possibility that his party might have moved by then, Pelly warns him to ‘look out en route […] for native craft & if one signal go to its aid’ (Mss Eur F126/43 f. 50r). Having made it to Charrack by 5 November, Pelly was by then clearly suffering from a lack of basic luxuries. Writing to Henry Christopher Mance, Superintendent of the Telegraph Station at Mussundoom [Musandam Peninsula], he requests: ‘Kindly send me by gun boat any cheroots you can conveniently spare’ (Mss Eur F126/43, f. 50v).

Telegraphic communication

Pelly had himself to thank in part for the submarine telegraph cable that had been laid in 1864 connecting Gwadar, the Musandam Peninsula, Bushire, and Fao (extending the overland line from Karachi). Some of his telegrams sent during this incident were probably forwarded via the telegraphic repeater (booster) station on what is now known as Telegraph Island [Jazirat Maqlab]. Whether any of them were received in time to expedite the rescue is unclear.

Pelly’s correspondence indicates that he also tried to contact the British India Steam Navigation Company, to make use of the mail steamers passing to and from Bandar Abbas. This would have hastened his communications and allowed him to collect any messages addressed to him.

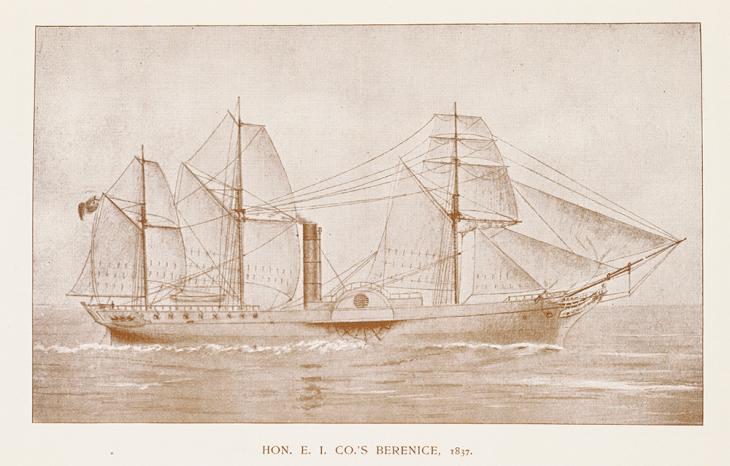

The steam ship Berenice

The Berenice had started her sea career as a mail steamer, transporting mail and passengers between Bombay [Mumbai] and Suez, Egypt. Built in Glasgow for the East India Company and launched in 1837, the Berenice was a naval sloop, wood paddle steamer, which could function under sail or steam, or both. At some point between 1845 and 1852 she was repurposed and became the Company’s first steam warship.

Charles Rathbone Low’s History of the Indian Navy, 1613-1863 indicates that she saw service in numerous military operations and conflicts, including the First Anglo-Burmese War (1852-1853), the Anglo-Persian War (1856-1857), and the ‘China Expedition’ [Second Opium War, 1856-1860]. Countless troop transports, sea battles, and repairs of a sometimes dubious standard all took their toll on the vessel’s condition. The Company’s ship Atalanta was launched in the same year and broken up around 1850, so Berenice’s best days may have already been passed when she was allocated for use by the Resident in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. . In a letter to Pelly, William Lockyer Merewether, Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in Aden, hints at this situation when he complains about the Government of India’s propensity for expenditure efficiencies: ‘That was an awkward thing the burning of the Berenice […] I hope they will now give you a good steamer in place of her. That Finance Committee in Calcutta is the devil, trying to do us out of our steamer vessels’ (Mss Eur F126/3, f. 26v).

However, it seems that the fire was not entirely caused by the poor condition of the ship. Writing to Frere on 19 November 1866, Pelly mentions that ‘the burning of Berenice was attributable to the stewards using naked lights in the orlop deck [the lowest deck], if not in the hold’ (Mss Eur F126/43, f. 54v). Between this and the faulty extinguishing equipment, Pelly seems to have been suffering a terrible run of bad luck. To make matters worse, he also indicates that the trip itself might have been based on a misunderstanding, without which ‘Berenice would have been saved and [Pelly spared] a week of considerable anxiety.’ Writing again to Frere, he says he was travelling ‘on what I supposed to be a special requisition emanating from your excellency’ (f. 53v). He does not explain the nature of this requisition, and the precise reason for his trip remains unclear. Evidently, while communications in the Gulf had improved by October 1866, there was still some way to go.